By Mark Oppenheimer

SEPT. 18, 2010, New York Times

The death this month of Seymour Pine, the vice officer who in June 1969 led a police raid on the Stonewall Inn in Greenwich Village, unwittingly galvanizing the gay rights movement, is a reminder that history has its forgotten actors, too. For every star in the history of gay rights — think the politician Harvey Milk, or the comedian Ellen DeGeneres — there are many more bit players, people whose names do not even make the credits.

In the world of religion, one of the great neglected actors, a man who had a marquee moment but then fell into obscurity, is the Rev. James Stoll, a Unitarian Universalist who died in 1994. Mr. Stoll, one of the first openly gay ministers in America, had a difficult life, and his demons seemed to follow him to an early grave.

But he was hugely responsible for introducing American churchgoers to gay rights. For those who support gay rights, he ought to be a hero; for those troubled by increased acceptance of homosexuality, he makes a vivid villain.

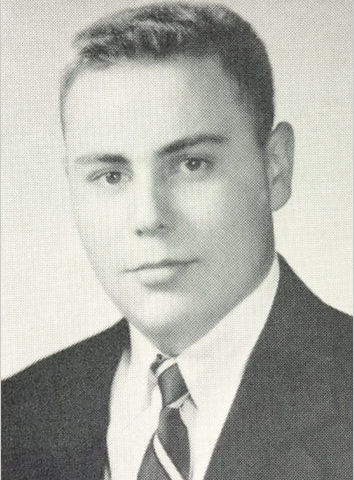

Mr. Stoll was born in 1936 in Connecticut. He was educated at Mount Hermon School, in Massachusetts, at San Francisco State University and, finally, at Starr King School for the Ministry, in Berkeley, Calif. After being ordained, he pastored a church in Kennewick, Wash., from 1962 until 1969. After leaving the church in Kennewick — church documents indicate that he was asked to resign — he moved back to the Bay Area.

In the words of Mr. Stoll’s friend Leland Bond-Upson, who in 2005 first delivered a sermon about him at a church in Petaluma, Calif., Mr. Stoll took a flat in the Eureka Valley neighborhood of San Francisco “with three others (me the draft counselor, Nick the cabinetmaker and Peter the communist revolutionary), and for a full year we four hosted an unending stream of young visitors, all come to look for America or something.”

Soon, in September 1969, Mr. Stoll drove Mr. Bond-Upson and two others in his Volkswagen Fastback to the La Foret conference center in Colorado Springs to attend a convention of about 100 college-age Unitarians.

“On the second or third night of the conference,” according to Mr. Bond-Upson, “after dinner, Jim got up to speak. He told us that he’d been doing a lot of hard thinking that summer. Jim told us he could no longer live a lie. He’d been hiding his nature — his true self — from everyone except his closest friends. ‘If the revolution we’re in means anything,’ he said, ‘it means we have the right to be ourselves, without shame or fear.’

“Then he told us he was gay, and had always been gay, and it wasn’t a choice, and he wasn’t ashamed anymore and that he wasn’t going to hide it anymore, and from now on he was going to be himself in public. After he concluded, there was a dead silence, then a couple of the young women went up and hugged him, followed by general congratulations. The few who did not approve kept their peace.”

Mr. Stoll was not the first openly gay minister. He had been preceded by at least one man, the Rev. Troy Perry, who the previous year had founded the Metropolitan Community Churches in Los Angeles. That denomination, which has straight members but has always specialized in ministry to queer communities, now claims 43,000 members in 22 countries.

But Mr. Stoll was a minister of an established denomination — a liberal one, often so diverse as to seem post-Christian, but nonetheless one with Christian roots. As such, he brought gay rights to the heterosexual Christian world. Over the next year, newly emboldened, Mr. Stoll wrote articles about gay rights and delivered guest sermons at several churches.

In July 1970, at their general assembly in Seattle, Unitarians passed a resolution condemning discrimination against homosexuals and bisexuals. Other churches soon liberalized, too. In 1972, for example, the United Church of Christ ordained an openly gay man, and today there are openly gay Episcopal priests and Lutheran ministers.

Having pioneered an important change in American Christianity, Mr. Stoll never returned to the ministry. In fact, it seems that he could not. According to letters kept at Harvard, sent in 1970 between church members and Unitarian officials, Mr. Stoll had been suspected of drug use and of inappropriate sexual advances toward young people in the Kennewick congregation. The circumstances of his departure made it unlikely he would find another pulpit.

Over the next 25 years, Mr. Stoll had a varied career. He worked as a substance abuse counselor, started a hospice on Maui, in Hawaii, and served as secretary of the San Francisco chapter of the American Civil Liberties Union.

“He died on Dec. 8, 1994,” Mr. Bond-Upson said in his 2005 sermon, “a little short of age 59. He died not of AIDS, but of worn-out heart and lungs. He was never able to lose much weight, nor quit smoking. When it was known he was dying, a stream of friends came to say goodbye. Friends arrived from the A.C.L.U., from inner-city social services, from Hunters Point, from drug abuse treatment centers, from the ministry. Yet despite all this matchmaking, and though his romantic side often found expression, Jim never had for long the all-embracing love he longed for.”

Mr. Stoll left no descendants, but he had many heirs.