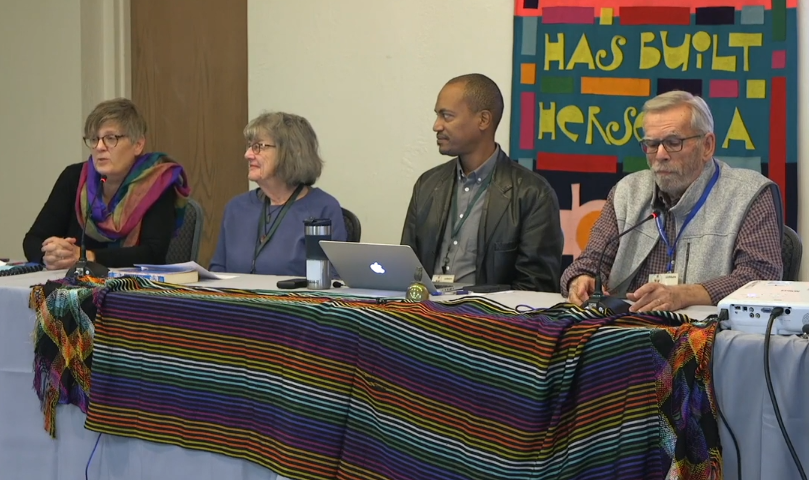

Lindi Ramsden, Lucy Hitchcock, Carlton Smith, and Craig Matheus

TRANSCRIPT:

Susan Rowley:

So I guess that’s my cue to begin our panel for this morning. As you can- Pardon?

Speaker 3:

We’ll get it.

Susan Rowley:

They’re working on it.

Susan Rowley:

All right. That’s my morning voice, but I can’t complain because Lindi is here and coming to us from California and it’s a lot earlier in the morning for her than it is for me. So we are delighted to bring you the second panel of the Yerba Conference and as you can see, we are highly technically and evolved here today. So we’re excited. I’m stepping in to moderate for Dee who was unable to attend and we’re all pulling together here. So this is going to be very cool. Oh, in case you don’t know me, I’m Susan Rowley Rak. And our panelists today are Lucy Hitchcock, Craig Mathews, Lindi Ramsden via Zoom and Carlton Elliott Smith. And we will follow the same pattern as we did yesterday with the panelists giving a… I will read a brief introduction and then they will be able to speak more deeply about why they’re here.

Susan Rowley:

So we’ll start with Lucy Hitchcock. Lucy grew up in New York, a Presbyterian and a girl scout. She married Charlie Miller, had two sons, became a religious educator and attended summer school at Starr King. Her marriage ended, followed by a few more relationships with men. She entered Starr King School for the Ministry where she met Patricia Woodward. While searching openly for a settlement and being continuously turned down, Pat came down with leukemia and died. In 1983, while partnership with Tamar Jad and in the closet, Lucy served in Bismarck and Fargo, North Dakota. After a year, Tamar joined her and she came out. There were some trying moments, but it all worked out. Lucy has since worked for the UUA, served in extension positions on the West Coast and ended her career with a healthy settlement in Miami, Florida. She had a commuter marriage for 11 years and is now single and retired living in Sill Work.

Lucy Hitchcock:

I’m glad to be with you to contribute to this transformative period in our history. I’ve been so moved many times since coming in. It feels like a return to another life in a way, but it’s been very rewarding. I came to Starr King and you’ll hear a little bit of repetition now. I came to Starr King in 1973 from Corvallis, Oregon where I was part time RE director. My mother died in 1972 and I was divorced in ’73, after a 10 year marriage with two school age sons. This was an era of emancipation and enlightenment and taking on patriarchy. It became essential that the courses in seminary alter their content and that women join the faculty courses in women’s literature, urban mock studies, goddesses and Mary Daily’s rewrite of theology proliferated.

Lucy Hitchcock:

At Starr King, we initiated The Aurelia Henry Reinhardt professorship and gained enough funding for the beginning of supporting it and it was to be filled by a woman. Seven Bay area women came together to start Chapel Street women’s meeting house, which included renting space for it. It was to explore women’s spirituality and communities, virtual community and practice new forms of worship. The content and style of ministry graduates helped to bring to congregations changed. Although I had several more liaisons with men, learning became my focus at Starr King. Close to graduation, Pat Woodward and I met at a psychodrama class, became lovers not without strife as we work towards living together. In this era of examining everything, loving and being loved by a woman felt very natural and very good to me.

Lucy Hitchcock:

I remember no hardship and letting people at Starr King know and I also notified my former husband and children that I didn’t have a problem there. My parents were deceased, I had no siblings. So it was as if I slip by coming out. I didn’t have many experiences. After ordination in 1978, I entered the search process. I was open about being in a relationship with a woman. My name was sent out to 11 congregations, full time and part time. I pre-candidated at several, all over the country. I was not chosen to be their minister. Some were explicit about not being ready for a lesbian minister. When asked if I would be willing to change my mind about being lesbian so then I could come. One said that a California type was not appropriate for their minister.

Lucy Hitchcock:

Meanwhile, Pat, who was a recovering alcoholic and who received a master’s in addiction counseling, apprenticed as a carpenter and took a job in heavy construction, climbing up high on the scaffolding and wearing a hardhat. She loved being one of the guys, but soon I had to leave the search process for over two years, because Pat was diagnosed with an aggressive form of leukemia. Chemotherapy drained her and in the end did not work. Her fighting spirit and her startling sense of humor kept her and her caregivers going. An older friend of Pat’s took us into her home. Pat returned to Catholicism with a very kind priest to encourage pastoral calls. Her family whom she had never told about her lesbian lifestyle, came for a visit from Detroit.

Lucy Hitchcock:

Pat and I being together was accepted by them and this was an important step for Pat. Interestingly, during her illness, Pat transformed from being butch to being increasingly fem. She even took to wearing a skirt, which if you had known her was amazing. She died at Teresa’s home, surrounded by friends. Her Memorial service was at a Catholic church in Berkeley. The women of Patrick Travesty carried her ashes to a bluff above the Pacific ocean. In 1987, I was invited by Bill Schulz to be part of the president’s colloquium at general assembly. And the topic is the body, the primordial sacraments. I wrote it as what I called narrative theology as a poem of tribute to Patricia Woodward. By request of the editors of this book, which is Redefining Sexual Ethics, it was published.

Lucy Hitchcock:

I had been rereading some of this and I read it stated, but I recommend you look at it. Given our topic, it’s very good. And it might actually give you some suggestions for the way our book comes together that we’re talking about. It has some good ideas. The poem begins. My lover’s bones lie scattered on a hillside in Mendocino County. It is a place made sacred by the pilgrimages of her friends. It took time to mourn, to discern what would come next. A caring friend, Tamar Jad became a new partner. I knew I wanted to leave the Bay Area. Too many attractions. Too many memories. I wanted a simpler life. A purpose, a vocation. Joe Goodwin came to the Bay Area to tell us about the new Extension Ministry Program and I got interested. Having gone to college in Minnesota, I applied, but, in the closet, Tamar and I agreed that I would go alone.

Lucy Hitchcock:

I was appointed, went to lead the congregation, was accepted and in 1983 moved to Fargo and his work. A two third, one third split, two houses, two old cars and took the bus 200 miles in between. Wonderful Midwestern folk. Fun to be a minister in congregations that wanted to grow, was involved with peace work, abortion rights and led classes in economic justice. The congregations grew. But after a year I was lonely for Tamar. She moved, we came out. Some congregants felt betrayed. Why hadn’t I told them before coming? Some thought that the reputation of the Bismark Fellowship would be ruined. One woman said that if she was seen out having lunch with me, she would be thought to be lesbian. This is conservative. It’s a conservative state and Bismark more so than Fargo.

Lucy Hitchcock:

Sid Peterman, district executive came to both congregations to be the you a standing behind me and it worked. No one left. They accepted Tamar. I was there two and a half years but I left early for the UUA, to teach others what I learned about growing congregations. Tamar and I ended our partnership after our move to Boston. Since then, I’ve been partnered, celibate and in a commuter marriage for 11 years to a very black male Muslim organic farmer from Senegal with two other wives. That’s a different story. I’ve been blessed with loving friendships and intimate relations with men and women in my long life. I’m not particularly wanting to be labeled as lesbian, bisexual, heterosexual, in some way that nothing fits and it’s not my central identity has a person.

Lucy Hitchcock:

I’m a mother, grandmother, minister, gardener and social activist now dedicated to saving our planet from global warming and mass extinctions.

Susan Rowley:

Thank you Lucy. We’re going down the list as I was given it. So next we’ll hear from Craig Mathews. Craig Mathews was born in Milwaukee, Wisconsin in 1951. He originally wanted to become a teacher, but when he realized he was gay, he thought he wouldn’t be fit to teach young people. So he left college in his junior year and worked at several jobs including his last at Northwestern Mutual Insurance. He met Tony Larson in 1984 at a gay bar in Milwaukee. They began a lifetime commitment in 1985 and had a unity ceremony on their seventh anniversary. Tony and Craig did not have any printed invitations or orders of service for this ceremony because Craig’s teaching career was just beginning. Craig and Tony are celebrating their 35th anniversary this fall. Craig, let’s here from you.

Craig Mathews:

Okay. Yes, I’m Tony’s husband and if you know Tony, I feel that I have to start with a humorous story. This is kind of folklore of our relationship. I knew Tony when I met Tony in a leather bar. I knew he was a minister, but I wasn’t sure what that all entails. So on our second date, we’re sitting in a restaurant and you’re just getting to know somebody and Tony looks at me and says, “Would you like to see me formulate the quadratic equation?” And I went, “Sure. Why not?” When we told this story to someone in our church at Olympia Brown, they yelled out, “And there was a third date?” So yes, there was a third date. There were many more dates.

Craig Mathews:

When deciding what to talk about, I thought I would talk about my personal experience in a medium size Wisconsin city of being diagnosed in heavy AIDS. And it had good experiences and then some that were not so good. In the beginning of the ’90s, we had planned a trip to Europe and it was a wonderful trip. But on that trip I started to be just not feeling great. I was tired and I couldn’t do a lot of the things. When we got home from this trip, I felt great. I felt fine. And I thought, “Well, it was the stress of being traveling in a foreign country.” About a year later, I did not feel so fine and I started to get a rash on my body and I was really tired and I had a difficult time controlling my bodily functions.

Craig Mathews:

So after talking with some people we thought I would go the route of… They said, “But are you allergic to something?” And I said, “I don’t think so.” So I went to an allergist, was a wonderful doctor and we were looking into allergies and things that might be affecting my health. And after one session with him, he said, well… He gave me the allergy shots and I couldn’t make it out of the office. I sat in the office and I couldn’t go from the office to the car. So I thought, “Wow, this is more than an allergy.” And he was a wonderful person. He came out and he saw me after sitting in the office for half an hour and 45 minutes and said, “I have a name of a doctor, I want you to see.” He recommended I go to my doctor who was wonderful, and he said, “I’ll make sure you get in to see the doctor right away,” which that just doesn’t happen even in the small town.

Craig Mathews:

So I called the doctor, the next day I had an appointment, and we went through all the tests and blood tests and things. And then he suggested I also get a chest X-ray. So I did. I went to the basement of the hospital and got my chest X-rayed. Later on in the day, I received a phone call from the nurse who did the chest X-ray. It was sort of clandestine. She said, “I’m really not supposed to be talking to you and I shouldn’t tell you this, but I think you have pneumocystis fibrosis.” Well, I mean, I knew that was a serious pneumonia that I had, but it’s hard as this is to believe as she’s telling me, it still wasn’t dawning on me that I had AIDS. That I was HIV positive. I just, “Oh, okay. Thank you.” Late the next day the doctor called and I hope they’ve changed the way they tell you. He told me over the phone.

Craig Mathews:

He said, “Oh, and the test came in and you’re positive, dah, dah, dah. I want to see you tomorrow.” Well, I’m in tears crying in the phone. Tony knew something real heard me crying, came into the room and we both cried for hours. So I went through the whole process and got drugs. Luckily for me, this was at the time when the drug therapy was changing. People, before me had to do these incredibly complicated drug cocktails or they would take sometimes up to 10, 20 pills and all sorts of different times. I did not have to do that because the Food and Drug Administration said that they would release some of the newer drugs without the testing that I could take them. That was right at the end of AZT and AZT was not working.

Craig Mathews:

And I remember we were in a vacation in New York City and again, I felt really tired. Things would go, spots were coming back. And I remember being in the hotel room, sitting there going, “AZT is not working.” And luckily at the time, the next visit to the doctor, I got different drugs. So I only had to take two pills once a day, which is a great thing. And they said that my viral load dropped. Originally, my viral load, which I call the bad numbers, was up to like 3,500 or just this incredible number. It’s supposed to be zero. Pretty much through the last 20 some years, my viral load has been zero, which is wonderful. It’s just great. And my T-cell count has stayed at about 500. Recently, that’s gone up.

Craig Mathews:

Unfortunately, the last time I went to see the doctor, he said, “Well, your viral load is no longer zero.” I said, “Oh.” Thinking it would be like two or something. And he said, “Well, we don’t worry about it until it gets to 200, then I’ll start looking at you.” And I said, “Well, where is it?” He said, “175.” I said, “Well, that’s close enough for me.” He said, “No, no, this will be a slower process.” And I trust him. He’s been just wonderful. So we’re waiting. A negative story about all this. When I first was diagnosed and I was filling my first prescription, we were at a large pharmacy. I won’t say which pharmacy, and we’re sitting in the lobby. I’d given the pharmacist the prescription. They took it and said to have the seat. In my mind, it was like that room was full of as many people as you and I’m sure there were maybe like six or seven people in the lobby.

Craig Mathews:

The pharmacists’ worker came to the window and instead of just calling me up, said, “Who’s here for the AZT?” And we both kind of freaked. We don’t go to that pharmacy anymore. Immediately, we didn’t go there. And I know that’s a reason for HIPAA laws. And every time I get a little annoyed with the HIPAA law, I remember that experience. So the other thing that I think is a big issue, and I don’t have much more information about it because I had a really good experience. I was a teacher and I had great health insurance and I had a great policy through my union. I had great benefits through my union that when I first was diagnosed, I couldn’t teach for a month, which is longer than I had start up for sick days. And the school system I worked for said that’s fine.

Craig Mathews:

Just when you come back we have to have a signed affidavit from your doctor about what was wrong and I was like, “Oh, I just wasn’t thinking, you’re all okay.” So when that affidavit came, the doctor put in HIV and Tony and I saw that and I said, “Well, I can’t be on there. I can’t go back.” I mean, they were a good system, but I don’t know how good they were going to be. And so Tony took that back to the doctor and they changed. They were kind of resistant and it was sort of like, “Come on guys.” And they did change it and they put down community pneumonia, which I just remembered. And then my school system just took me back and it was great. But any expense that I have experienced has been covered under my great insurance at the time and now under Medicare.

Craig Mathews:

So that’s another big issue I think with healthcare and people that don’t have access to that. I mean, I don’t know what we have done if we didn’t have that. So that’s my experience and I see the doctor again in, sometime early November. And the other thing I should say, Tony is not HIV positive. There are many different brands that you can get. I have a less virulent type of HIV, so it’s been relatively easily treatable and not very communicable. So even when I had it, they figured before my diagnosis, I had it for probably 10 years and I wasn’t particularly promiscuous, I don’t think. I think I just had sex, like young men had sex. So we all lucked out. Tony lucked out, even with our sexual activity, he did not get it.

Craig Mathews:

And Tony also had to be tested for it. That was another nerve wracking thing. Oh, another thing that we did that was nerve wracking, it’s all this stuff that it’s happening to you and you’re really like, “Oh, my goodness.” And it was okay. I understood now, we had to go to the public health office in Racine, which was in the basement of the city hall. And it’s like you’ve just been diagnosed with this disease. You think you’re going to die and now a public health nurse is taking your name down as a public risk or something just as a record. She was wonderful. She was really a wonderful person. She just knew how to handle it and I think she lives down the hall from us. So now at her condo where we live and she’s just a really nice neighbor. So that is my personal story of living with AIDS, living with HIV in a medium sized town in Wisconsin. I have other stories.

Speaker 7:

We want to hear the dirt on Tony.

Craig Mathews:

What?

Speaker 7:

We want to hear the dirt on Tony.

Craig Mathews:

Well, I’ve got one more goofy story. This is bad. We’re like maybe our third date. And again, I knew he was a minister, but I was not a Unitarian. I was raised ALC Lutheran, the good ones. And so again, we’re in a restaurant and he looks at me and he said, “Are you religious?” And I thought, “Come on, he’s a minister.” And then I thought, “Well, if we want this relationship to go anywhere, I should be honest.” And I said, “No.” And he said, “Oh, good. Neither am I.” And apparently he had had several… Sometimes I think people are attracted to ministers and then there’s a whole, they’re more religious than the minister. So anyways, so that’s the only other dirt I have. Otherwise, I have to say this, having a partner is better than life insurance, having a partner who’s there to take care of you and it’s just incredible. So thank you.

Susan Rowley:

Thank you Craig.

Thank you.

Susan Rowley:

Thank you. Moving right along. We’ll get to questions eventually, but this is just wonderful sharing and hearing each other’s stories. Resuming into Lindi Ramsden. Lindi was ordained in 1985 at the First Unitarian Church of San Jose, California. Lindi went on to serve that congregation for 17 years. During the following decade, she served as the executive director and senior minister of the UU Legislative Ministry of California, engaging California UUs in organizing an advocacy on behalf of marriage equality, immigration reform, and securing the human right to water. Currently she is working on the staff and faculty of Starr King as Director of Partnerships and Emerging Programs and is the assistant visiting professor of faith and public life.

Susan Rowley:

Her personal calling during her final years in ministry is to better prepare seminarians to more effectively serve during a time of increasing climate disruption. She and her spouse, Mary Ellen, were married in a religious ceremony in 1992 and they were able to make it legal in 2008. They feel blessed to be parents of a grown son who embodies his Unitarian Universalist values. Lindi.

Lindi Ramsden:

I am trying to reduce my carbon footprint. So I’ve been taking the train lately and it’s a long trip from California to you guys and back. So I really appreciate being able to join you remotely. When they sent out the invitation to talk, there was a question about how you’ve noticed some experiences in your own life might have impacted the arc of Unitarian Universalism. And I feel like I’m sort of a reluctant lesbian. Lucy’s comment about it not being central to my identity kind of hits home to me in a certain way. It is my identity and so it is central and obviously my family is central, but it wasn’t really what I wanted to do in ministry necessarily. But in watching what happened over time, I do feel like I’ve seen ways in which the UUA ended up setting a boundary around how our congregations were going to deal with us as candidates through ministry.

Lindi Ramsden:

And I also saw that the work around rights for gay and lesbian and later bisexual and transgender folk help to strengthen and move us into more regional and statewide kinds of collaboration. So in my own story, about 50 years ago, 1969, I was a sophomore in high school, I was an active member of a UCC congregation and I was already thinking about ministry. And I remembered going to the Northern California conference in the United Church of Christ in Asilomar, a place known to the UUs as well. And Bill Johnson, who in 1972 became the first openly gay person to be ordained in a Christian denomination was a very important part of that conference. And I remember feeling very supportive of his cause. He was having a difficult time finding a place to actually serve in ministry. But I didn’t realize at the time that it would become so relevant to my own life.

Lindi Ramsden:

And then once I got to college, I basically studied my way out of Protestantism and I also figured out I wasn’t straight. And the combination of those two revelations about myself, I thought, “Well, I guess I’ll just set aside my plans for ministry.” It didn’t seem like it was something that could happen with integrity. And so I changed from studying religious studies to human biology, which was another way of, “Isn’t life amazing and how does it all work?” But I still had this deeper pole and questions of meaning and purpose and in my life. And as luck have it, my friend and mentor Ann Heller enrolled at Starr King and I started meeting people like Lucy and others and Mark. I came to know her seminary friends and just witnessing their depth of spirit and intelligence and rollicking creativity.

Lindi Ramsden:

And the fact that several of them were gay or lesbian signaled that there was a seminary where the door could be open to someone like me, both someone who was a lesbian and who was not theologically in the street in their own. So I kept my day job and enjoyed seminary. Not so much thinking that I was preparing for careers. I was watching folks like Lucy and Anne and Barbara have a difficult time finding a place to actually serve. I just went from my own spiritual growth and kept working at my job, so as not to end up in debt. But in 1983 at the invitation of Rah Beller Isaac, I was offered the opportunity to serve as an intern minister at the First Unitarian Church of Oakland. And there I really had the opportunity to fall in love with the power and possibility of parish life all over again.

Lindi Ramsden:

So I decided to go ahead and throw my hat in the ring and see if there was a parish ministry where I could work. And there wasn’t much luck going through the normal channels. So similar to Lucy’s story, except that I was able to actually be out of the closet when I applied. The Extension Ministry Program was what got me placed in the First Unitarian Church of San Jose, which was at the time a small struggling congregation. I think their pledge base was like $28,000 or something at the time. It’s a beautiful building, but they had fallen on hard times as a congregation. In watching on Chuck Gaines in particular, who had attended what we called the fruit bowl, there was a gathering at the Unitarian Church in Oakland during that period of time where the UUA was really trying to figure out what to do. Because they felt like there was talent staying on the table that wasn’t able to be put to use in good service to our congregations, because people were afraid to have gay or lesbian ministers there.

Lindi Ramsden:

And I feel like the UUA just really decided at that point they were going to figure out a way to make it go forward. And so the Extension Ministry helped to place some of us. And then a few years later, Jackie James and myself and others put together what was called the Beyond Categorical Thinking Program at the time, which was in some ways an early step into intersectionality. We just didn’t have the language. I didn’t have the language anyway for it at that time. And they’d send us out in teams of two, representing different kinds of folk, people of color, LGBT people, older people, disabled people, to work with search committees to help them deal with all of their internal conscious and unconscious biases before they were able to get a list from the UUA. So this was the UUA in my mind stepping forward to move us into a different place.

Lindi Ramsden:

But as I said, I feel like I was interested when I got to the church more in the sanctuary movement, other kinds of things that were going on. But our church ended up winning this award. It was the OEG and Pickard Award on church growth and the local San Jose Mercury News wanted to do an article about the church. And I thought it would be just like a small article in the corner, but one of the things I wondered about was how the people actually felt about having a lesbian minister and whether they felt like they were ready to be public. I remember my mom and dad, when our son was born and adopted, it was one thing that they were accepting of me as a lesbian in our family, but then they started telling their friends that they were grandparents.

Lindi Ramsden:

And so there was a way in which they had to come out to their friends as well as a result of that. So by the fact that our church was going to be acknowledged in the local newspaper, meant that the people in the congregation had to take another step in a way of coming out. Like, I’m a person that goes to a congregation like that, which right now sounds like really a ridiculous thing to be worried about. But back in the late ’70s and early ’80s, in California, we had the Briggs Initiative, which was essentially trying to quarantine people with AIDS. We had another initiative that was trying to prevent people from being teachers if they were gay or lesbian. There were two ballot measures in San Jose which overturned by very large majorities, protections that had been put in place for LGBT people by the city council and board of supervisors.

Lindi Ramsden:

So it was a very hot political climate. And I had not preached much at all in the first three or four years that I was in ministry about LGBT related issues other than to not be in the closet about having a female partner and our son. In part, because I had heard from women ministers who had broken the gender barrier in ministry prior to me, talk about how if you preached on feminism more than a couple of times you’d be accused of being a single issue person. They’re like I wanted to be a single issue person, but here I was about to have this article in the paper. And I thought, “I better ask these folks what they think.” And so at the very end of the service, I just stopped and I explained what was happening.

Lindi Ramsden:

And I asked them, I said, “So how do you feel about doing this article together?” Which in a way was another layer of coming out for the congregation and people just rose up and started clapping. And it was the most amazing affirmation of their willingness to go to Hewlett Packer and go to wherever they were working and feel like they were in the paper. And so we went ahead and at the time there was a large religion and ethics section in the newspaper, two full pages, if you can imagine that in this day and age. So there was this gigantic article about us as a family and the church. And the next day there were 100 new people in church. This was from a very small congregation. They called themselves the people of the article.

Lindi Ramsden:

So there we were together and we kept up, which led into additional engagement in terms of social justice work. I remember when proposition 22 was placed on the ballot in California which was trying to amend the family code to prohibit same sex marriage in California, this was in year 2000. And Rob Hardies was, I think a student minister at the time or just a student at Starr King and went around and organized a bunch of the Bay Area congregations to take out a collective ad against this, which was one of the first times that I saw local congregations really putting themselves into essentially what was a political sphere. When I was working on the statewide effort to defeat prop 22. And when they found out that our congregations had agreed to do this and they were putting it in the San Francisco Chronicle two weeks before the election, basically what they said to me was, “Are you nuts? You have that much money? Could we please spend in Modesto? Anybody who reads the San Francisco Chronicle already knows how they’re voting two weeks before the election.”

Lindi Ramsden:

And I thought, “You’re absolutely right. I don’t disagree with that,” but what this was in many ways was less an effective ministry on our own, but more of a statement to ourselves of being willing to step ahead, be public and organize together. And I feel like that initial effort, while it was flawed in some ways also led to what eventually became the UU legislative ministry in California, which later led to our being very much involved as the leading organization. Because we had a 501C4 as well as a 501C3, to coordinate the No on prop 8 campaign in California among all the faith communities. So our little tiny office, we were like drinking from a fire hose trying to figure out how to do all this, was responsible for 13 different phone banks and outreach efforts.

Lindi Ramsden:

In terms of educating around marriage equality, it was absolutely nuts. And we learned a lot in the process, but I feel like the marriage equality movement in some ways took a hold of our congregations, because it was something they felt like they had a personal interest in. And move them into another layer of social justice engagement and political activism. As was mentioned in my introduction that Susan read, I did get married to Mary Helen in 1992, thanks to Mark Bellatini and Harry Scofield in a ceremony that wasn’t legal. But in the little window between when marriage equality was declared legal by the court report in California and before Proposition 8 passed six months later, which voided everything. We did finally get to make it legal and we weren’t sure where we should get married.

Lindi Ramsden:

We already had a wedding. We just wanted to make it legal. But secretary of state, Debra Bowen was a Unitarian Universalist who had grown up in Illinois and she had been helpful to us in the UU legislative ministry. So I called her up and I said, “Any chance you would consider doing this for us in a small private ceremony?” And so sure enough she said yes. And my son and my mom and Mary Helen and I got married overlooking the Capitol on the first day that you could be married in June of 2008 and Secretary Bowen made it legal. And I felt like finally that part is done. Let’s move on to working on some of the other things that I care about. So there are many more stories to tell. Governor Schwarzenegger, all kinds of variety of things, but I’ll save those for later in questions and answers. And thank you for listening.

Susan Rowley:

And our fourth panelist is Carlton Elliot Smith. Carlton is one of 11 members of the UUA Southern region congregational life staff, based out of Holly Springs, Mississippi, his hometown. He was recently a candidate for the state senate. As such, he was endorsed as a spotlight candidate by the LGBTQ victory fund. Ordained into UU ministry in 1995. He has been a parish minister in Metro New York, Greater Boston, Northern Virginia, and Oakland, California. Carlton was one of the original members of the black lives of UU organizing collective and had the vision that led to the $5.3 million bequest, requests that Blue made of the UUA board. A commitment which was fulfilled this summer. Carlton.

Carlton Elliott Smith:

Thank you, Susan. And I’m very grateful to be part of this panel. So I’ll share three brief stories as my contribution to the UU LGBTQ IAA history archive all in the last few years. Story one, the record should reflect that three of the original members of the organizing collective of black lives of Unitarian Universalism, also known as Blue, were LGBTQ IAA. Lina Catherine Gardner, now Blue’s executive director, Andrea Williams, now co-moderator of the UUA and me. I attended the movement for black lives convening otherwise known as the M for BL at Cleveland State University in July of 2015, as a member of the UUS congregation on my staff and with the support of multicultural group, the multicultural growth and witness office, MGW.

Carlton Elliott Smith:

My task was to informally organize the UUs in attendance of which there were about a dozen out of 1400 participants. Out of three meal time meetings with a handful of black UUs sprouted a movement for reform inside the UUA. After months of intense organizing and imagining among those of us in the organizing collective, Leslie McFadden now on the UUA board and I, made the proposal to the UUA in October of 2016, that resulted in its commitment to raise/donate 5.3 million to Blue. Though I discontinued my involvement in Blue by the end of that year, I’m grateful for all the ways that Blue has caused growth and transformation in our association, in our congregations, and in individuals including myself.

Carlton Elliott Smith:

Story number two, the record should reflect that one of the UUs on the front lines of the clergy counter protest to the unite the right rally in Charlottesville, August 12th, 2017, was a gay black minister from Mississippi Unitarian Universalist. That was me. Congregate Charlottesville, a group of local clergy had sent out the call for clergy from across the nation to join them in opposing the radically racist national gathering happening in their city. UUA president, Susan Frederick Grey had committed to being there. I was already in Virginia with my Southern region teammates at a leadership training event the week before and drove up to Charlottesville picking up Reverend Susan from the airport.

Carlton Elliott Smith:

There are many details of that weekend, but this one stands out. Those of us who marched, were well aware that when we stepped out onto the streets that Saturday morning, we were at risk of being severely injured and even killed. I locked arms with Dr. Cornell West on my left and Reverend Susan was a few people to his left. We prayed, chanted and sang in front of the Robert E. Lee statue in Emancipation Park, as wave after wave of supremacists taunted us upon their arrival. Heather Heyer was murdered that afternoon when a racist plowed his car into pedestrian counter protestors. Reverend Susan and I were just driving away when that chaos erupted. We knew that, that could have been us.

Carlton Elliott Smith:

Story number three. The records should reflect that with tremendous moral support and substantial financial support from UUA colleagues and UUMA colleagues, clergy and otherwise, a gay black union minister became a significant candidate among North Mississippi Democrats starting with the 2018 midterm elections. I ran for US Congress seeking to represent Mississippi’s first congressional district. However, I failed to make an important deadline and didn’t make it onto the ballot. I ran for State Senate District 10 in 2019, placing second in each of the two constituent counties, but third overall. Nonetheless, I gained the endorsement of the LGBTQ victory fund as was previously mentioned and outbound raise the other three candidates combined by a factor of 20.

Carlton Elliott Smith:

All that I learned and all the contacts I made during the incomplete congressional campaign became the foundation for an exceptional run in the state senate campaign. I applied for another election and very grateful for the opportunities that call me forward. I’m currently a member of the LGBTQ Victory Fund Campaign Board, which identifies recruits and fundraisers for LGBTQ candidates.

Susan Rowley:

Thank you Carlton. Now we only have about 20 minutes before it’s break time. And I noticed I had a list of questions similar to the questions that were asked yesterday and a lot of what’s in the questions has been covered in what’s been shared. But I’d like to put it out there, because our panelists experiences have been very different with respect to congregational life and public life and personal life. And so I’m going to throw it out to you to try to make sense of this question. In your experience, what problems have arisen inside congregations as much as you know inside congregations that appear to be linked to this or whatever organizations you’re been part of, that appear to be linked to discriminatory attitudes against ministers or their partners who are LGBTQ IA.

Susan Rowley:

Such as accusations of preferential hiring or refusing to accept you as their minister or refusing to include you as a partner as part of the social life of the congregation or microaggressions you might’ve experienced. And this might be stuff long ago in the past, but it’s things we need to capture and it might be things you’ve experienced recently, like last week. Anyone.

Lucy Hitchcock:

My answer’s not really-

Susan Rowley:

Go with it. I mean here. Go.

Lucy Hitchcock:

My answer’s really to a different question. I’m sorry.

Susan Rowley:

No, do it.

Lucy Hitchcock:

But I really want to say it. I became the Extension Ministry Programs director at the UUA and I was very aware of how hard had been for me to get a congregation. And I knew about all of these categories you’ve heard of that were affecting who was coming into the ministry and that really impacted congregations and how they met folks that were applying. In the extension department, it’s a different settlement process. So I would visit the congregations, get to know who they were, meet the ministers who were applying and make matches. And the congregations needed to know that I could not discriminate on the basis of any of these categories. So I would make my first visit to the congregation would be to explain this to them and I started a process, you’ve heard about elsewhere.

Lucy Hitchcock:

I had index cards that were green and pink and I asked the members of the congregation, after explaining who was in the pool, on the green cards, what would be positive about having any of these folks come to your congregation, who were gay persons of color, had disabilities, were female. It was very female. Females were just coming in to the ministry and then on the pink card, anything that they felt was difficult for them or for their community, for their congregation, and to write it. And all of this was anonymous. They passed the cards back in. And after a break I would read back to them what they had written.

Lucy Hitchcock:

There were very positive things said. People were excited to be on the forefront of inviting different categories to be their minister. Some of them were cautionary about their community, their community would have a very difficult time accepting someone who was gay or someone who was African American. And some of them were repugnant, the only word I can say. They were blunt, they were candid. And in a sense that was good because we knew who was there. This was especially true for African American ministers, somewhat true for gay and lesbians. And it was impactful to me, certainly and the UUA to realize what was out there and what we had to deal with. I put that in because that was the beginning of what became categorical thinking, was extension was able to bring this because we could not discriminate.

Lucy Hitchcock:

I also want to mention that the UUA was brave in many ways and the staff was really behind all of this. And we also started new congregations that were planted in African-American areas for African American ministers. And this gets lost sometimes, but there was a lot of funding for that. And they were also supportive, as you’ve heard before, through lesbian ministers and so forth. But they invested, with the beach money behind it, I can’t say what’s happened to all of those congregations, but we were trying our best to do something really revolutionary within our movement, to change the character of who was out there and how we served.

Susan Rowley:

And that was when? ’80s?

Lucy Hitchcock:

I went in ’85, I went. So it was the late ’80s that this was beginning. Well, the new congregations began before that, with Tom Chulack and John Morgan and so forth.

Carlton Elliott Smith:

Yes. And I would add that I was one of those extension persons as well. I came into the association through Alma Faith Crawford. Actually it was one of my classmates at Howard University School of Divinity. I went to Sojourner Truth Congregation, which was an extension congregation at the time. [inaudible 00:55:13] and maybe as far as [inaudible 00:55:15] our professor at Howard was speaking there. And I saw the principles and that is what really inspired me and said, “I could go for a religion like this.” I was wearing out my welcome at the Pentecostal Church I was attending as a young adult. But I’m thinking about like… So it cuts both ways because I knew from Alma at the time that the Extension Ministry Program was intentional about welcoming in ministers of color and other marginalized groups.

Carlton Elliott Smith:

So there were some doors that opened as a result of that. And then once inside the system it’s like, oh, but not, all those doors aren’t as open as they look from the outside. It was what I found out. So as the hymn in our hymnal says join a wall or woven fine, so I can see that those two things kind of intertwined. I know that when I worked at the Hollis Unitarian Church in Queens, the older members there were concerned that I was trying to turn it into a gay church. and that was a bit of a stressor. And I think there’s a way in which for ministers of color and other marginalized groups, there are yet ways in which we are experimented with, that doesn’t necessarily happen with other ministers.

Carlton Elliott Smith:

So there’s a risk people are willing to take with that. So I’ll just give like a little example. There was a point at which I was serving as assistant interim minister in Arlington, Massachusetts and there was another minister, Chester McCall who was serving as assistant interim minister at another congregation in San Diego, if I’m not mistaken. And so the question was, well, if you already have a congregation that’s willing to accept an interim minister as a person of color and there’s difficulty placing people of color anyway, well, why not give those congregations an opportunity to have that minister, that interim assistant serve in that position.

Carlton Elliott Smith:

So there was a temporary suspension of the three year rule, so the reason this could apply for those positions for two years. And that’s how I ended up being at Arlington Mass for a total of six years instead of the initial two that I was interim. Chester ended up not going to San Diego. I don’t know exactly what happened there. Then the second year came around and there was yet another minister who had the possibility of continuing on in that interim position. No, of applying for a settled position, even though he started out as an interim, put it that way. And that didn’t go very well. And I don’t think there was ever any real follow-up to see like how all of that played out. Even for me in my situation, I would say out of those three situations, mine turned out the best, but it was no cakewalk either.

Carlton Elliott Smith:

So I think we need to acknowledge that, yeah, we still get experimented with and there are not particularities in ways that other ministers don’t. And that suspension applied for ministers of color serving as assistant ministers of religious education. It wasn’t a big top position. You couldn’t be like one of those top positions and get that. So there was a ceiling, of course.

Craig Mathews

Well, my experience at Olympia Brown Church was that they were-

Craig Mathews:

… in Wisconsin, is that there were… In my church, that Olympia Brown church, they were very supportive-

Speaker 3:

Louder.

Speaker 4:

We can’t hear [

Craig Mathews:

That the Olympia Brown Church that I went to-

Speaker 3:

It’s still low.

Craig Mathews:

No.

Speaker 4:

It’s not close enough.

Craig Mathews:

All right. Now we got it up. That the Olympia Brown Church was very supportive. But I have to also be honest and say I never told the entire congregation about my health status like I’m telling you. And I told friends and I mean a significant number of people knew, they were very supportive. And then the other big credit, my life as a teacher, I was really active in the Racine Unified Teachers Union as a building rep for 10 years. They were so supportive and they had all kinds of things in place for someone like me or other people who were not going to have traditional things happen in their lives. And one of the things was I taught fifth grade and a parent went to my principal. Now I never told the kids. The kids would say things like, “Are you married?” And I would say, “No, are you?” And then they were just…

Craig Mathews:

So it never became like an issue with either the family or the administration, but I just think after you were teaching at the same place for 20 years, they know you. Anyways, a parent, went to the principal in my building and said, he did not want his daughter to have me because he knew and the principal who never did this kind of thing said, “Okay, I’ll take your daughter out of the class.” And then he said, “Thank you, I would like to thank you for that.”, “Oh, don’t do that. I didn’t do it for you, I did it for the teacher. He doesn’t need to deal with this.” Where that came from, from that principal, I have absolutely no idea, but it was great. I mean the union was so supportive. One time we were going on vacation and my pills were running out and the person from the school said I had to tell her what she would put down to let me get my medicine out earlier.

Craig Mathews:

But she had to know what it was for and what the things were. And I knew her and I didn’t think that she was going to do anything bad with that information, but I thought, “Really? It’s not your business.” So I went to the union people and they went and talked to her and all I had to do is give them numbers. So unionism and insurance are just so important and they both seem to be, I think it’s really been attacked in Wisconsin and Racine in particular. And we all know what’s happening with insurance. It’s just such an issue. So that’s my experience with the two important parts of my life.

Speaker 3:

Craig, could you tell about the parent that didn’t want the kid and then you taught them family life?

Craig Mathews:

Oh, that was another cool thing that district did was they had helping teachers and you could go to those when you first were starting. They would come to you and they’d say, “What would you like me to teach for you?” And you could pick math or science or whatever and they would do a couple of lessons. Well, this was right after I had come back from my illness and family life was coming up and I was the male teacher. So I got family life for all the boys. And so the helping teacher came and said, “What would you like?” And I said, “Would you teach family life for me,” and it was six, one hour lessons and he came every day and taught all the family life for me. And I’m pretty sure he was gay also, but it was just wonderful. Is that what you meant?

Speaker 3:

No, the dad who didn’t want his kid taught by you got family life by you.

Craig Mathews:

Oh, yeah, that’s right. The parent that complained about me did eventually I had to teach his child family life.

Susan Rowley:

How did that go?

Craig Mathews:

I mean, fifth graders are little kids there. It’s not like the topic they’re going to be real vocal about anyways. So it turned out to be fine and we have a strong and very accurate AIDS part of the curriculum, which was a little bit hard to teach once I had to turn to the chalkboard and just kind of like pull it together and then turn back. And that was again, I think all because of the union and teachers are wonderful people. Anyway, so I had to know who out there as a teacher or with a teacher. I mean, they’re pretty with it in general.

Susan Rowley:

So there are-

Susan Rowley:

Pardon.

Lindi Ramsden:

I was just going to add in a word. I felt like in my own congregation, I was just incredibly warmly welcomed. I think that was I’m white, I don’t come across as gender queer. There’s so many class and racial issues that I didn’t have to carry with me as I went into ministry. So I felt like that made it easier for me. When I look at students now coming out of Starr King and the young folks who are very much more identifying as non-binary, as gender fluid, as trans, as gender queer. There’s a whole other layer of work going on there that needs to be done within our congregations as people try and understand who they are and get their minds around simple things like pronouns and more complex things around the nature of reality.

Lindi Ramsden:

And when that intersects with other things, race, disability, some of our folks really have amazing talent and reminds me of our own earlier story of trying to step across some of those barriers to be able to be taken in and respected fully as ministers and community. I did feel like in the larger community, it was always a moment about trying to decide when to come out, and when not to come out. But when we started the Spanish speaking ministry in the San Jose Church, it was actually connecting in many ways with the Spanish speaking LGBT community. So I felt like it created a positive linkage and one of the most amazing experiences in my own ministry was helping to facilitate and owning your religious past weekend for Spanish speaking LGBT folks, who were really looking at religious wounding and what that meant for them in their lives. And it was just such an amazing privilege to be able to be part of helping to make that happen.

Susan Rowley:

Thank you Lindsay. And that was kind of where I was going to wrap things up because as I was listening to everyone, I was thinking about what we learned from the past, our own experiences and even the very recent past, what does that alert us to for the future? And Lindsay sort of hinted at it with or flat out mentioned it with the new generation coming out of seminary, looking at our congregations, that even more recently how our congregations are reacting to even shifts in language. Even as an interim, setting out a moderator role because I just wanted to share this because they were looking at a packet and their candidate identified as queer.

Susan Rowley:

And as the interim, I had to take them through the whole process of what does queer mean. And I couldn’t define it for the candidate, but I could help unpack their thinking and broaden the scope. And my interim training didn’t explicitly prepare me for that, but that’s the kind of stuff. If anybody has any last thoughts, you want to jump in before we have to take a break, but we’re forced by the clock —